Excerpts from the blog of his grandson, RickOnTheater

Harry Freedman (1896-1967), made dolls for a living.

Harry, on the other hand, who was only 5′ 4″ tall, was known by his business colleagues as “Little Caesar.”

Harry was a World War I vet. He fought in France and was wounded and so he was sent home prior to Armistice Day (11 November 1918)—before most of the other Doughboys came back. Having recovered from his wound, he was one of few able-bodied young men in the States while the war was winding up in Europe. He began looking for something to do with his life.

Many years earlier, when Harry was a boy and vehicles on New York City streets were still drawn by horses, he was hit by a city garbage wagon and slightly injured. As compensation for the accident, the city paid him $10,000, which was a mighty sum in those days (about $250,000 today). The money had been put aside for his future, as people used to say, but now Harry, in his early twenties, decided it was time to put it to work and start that future. The budding businessman started looking for something worthy of his investment and he found a company: the Regal Doll Manufacturing Company of New York City, known as the German American Doll Company before the war.

It was a going concern, with plenty of orders and a busy factory on West Houston Street at the southern edge of what is now NoHo, but it needed capital to buy raw materials to fill the orders. So Harry bought into Regal Doll and became a partner, eventually taking over leadership of the business. After a few years, Regal Doll Manufacturing changed its name again, becoming the Regal Doll Corporation.

Before the 20th century, dolls in the U.S. were almost exclusively imported from Europe, most frequently from Germany. Even when American companies started manufacturing domestic products just after the turn of the century, the materials were brought over from Europe. World War I disrupted that supply chain and the American doll manufacturers like Regal began making a product based largely on local materials. So when Harry invested his nest egg in Regal Doll, it was ripe for success, and the company prospered, making a good-quality, popular-priced doll.

In the middle of the 19th century, dolls—really the doll’s heads and sometimes the hands and feet—were made of porcelain, either china (shiny and not very realistic-looking) or bisque (matte and much more lifelike). Homemade dolls could be made of rags, corn husks, carved wood, or any available material, but manufactured dolls were porcelain—and they were highly breakable, a serious drawback for a child’s toy.

A major improvement came along as early as 1877: the composition doll. Made of a composite of sawdust, glue, and such additives as cornstarch, resin, and wood flour (finely pulverized wood), composition dolls had the great advantage of being unbreakable, and by the beginning of the 20th century, composition dolls were the most popular kind of doll on the American market. Horsman (which would be Regal’s successor) secured the rights to the process, which was the principal material for dolls from about 1909 until World War II.

In the ’30s, Regal made a 19-inch-tall doll with composition shoulders and head, composition arms, partial composition legs, cloth stuffed body and stitched hips. The head had molded, painted hair; blue tin eyes; and a closed painted mouth. The doll’s name? The Judy Girl Doll. Harry’s daughter and the mother of the author Rick, was named Judith!

Later that same decade, Regal marketed a 12-inch-tall all-composition doll with a jointed body and painted, molded hair; painted blue eyes; and closed painted mouth that came in a cardboard carrying case with a wardrobe and roller skates. This doll also came with “sleep” eyes, or “open-and-close” eyes, and a mohair wig over her molded hair. This baby’s name? Bobby Anne. Judith’s little sister was Roberta Ann and called Bobby.

By the ’30s, however, Regal’s Manhattan factory was no longer adequate for the growing business and Harry went in search of larger facilities for his burgeoning company.

He found the Horsman Doll Company, the oldest doll-maker in the United States established in New York City in 1865 by Edward Imeson (E. I.) Horsman (1843-1927). “No other company even comes close to its record of longevity,” says a corporate description on Zoominfo. E. I. Horsman had retired in the early years of the 20th century and turned the company, one of the pioneers in the manufacture of American dolls, over to his son, but Edward, Jr. (1873-1918), died suddenly at 45 and E.I. returned to the business. Then E. I. Horsman died in 1927 and the previously greatly successful company fell into serious financial trouble.

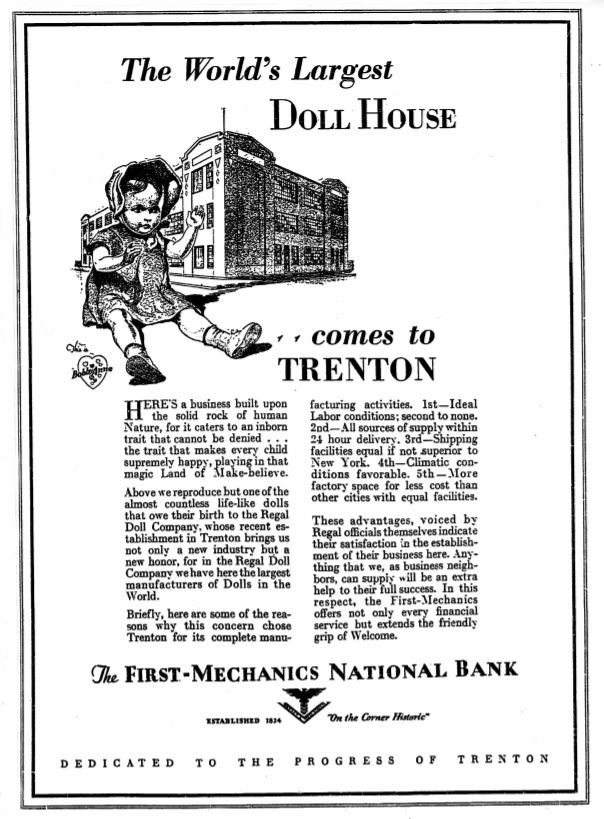

In the early 1930s, Regal built a large, in the Chambersburg neighborhood of Trenton, New Jersey. Regal, now under under the direction of Harry Freedman and his chief salesman, Lawrence Lipson (1896-1959), acquired the nearly bankrupt Horsman Doll in October 1933.

The new leadership and Regal’s solid business position revived the fortunes of Horsman (whose name was pronounced like horse-man and whose logo was a horse’s head) and the new company continued to make dolls under both trade names, Regal and Horsman. Regal produced a mid-level, less-expensive doll, while Horsman’s product was a higher-quality doll at a slightly higher (but still affordable) price.

By 1937, however, Harry Freedman and Larry Lipson realized that Horsman was the superior brand and in 1940, Regal Doll formally became Horsman Doll and the Regal label disappeared from the market. (The present-day Regal Toy Company of Toronto, Canada, is a different company unaffiliated with Regal Doll.)

At the time of the purchase, Harry’s family moved from the Upper West Side of Manhattan, to Fisher Place on the Delaware River in downtown Trenton, so Harry could be near his business, a scant three miles away. The new company’s business headquarters was still located in Manhattan—in the Toy Center South, which had become a home base for the toy industry during World War I. At the end of World War II, Harry and his family move back to New York City.

Regal and Horsman weren’t the only toy makers in the Garden State. From about 1880 to the end of the 1960s, the State of New Jersey was one of the country’s most productive toy-making states. There were over 50 toy companies operating in the the state with names like Tyco (HO scale toy trains), Lionel (model trains), J. Chein (mechanical toys), Remco (remote control toys), Topper Toys (model cars and inexpensive dolls), Courtland (wind-up toys), and Colorforms (creative toys) operating in the state. Regal and Horsman weren’t alone in the Garden State.

One block square, at its peak the two-building, three-story brick complex at 350 Grand Street in an otherwise residential neighborhood of South Trenton employed 1,200 workers and manufactured hundreds of thousands of dolls every year, earning the nickname “World’s Largest Doll House.”

“Not many people realize it, but if you purchased a doll from 1930 to 1960 it was probably made here in Trenton,” says Nicholas Ciotola, curator of cultural history at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton, where there was an exhibit called Toy World from October 2016 to April 2017 focusing on the toys manufactured in New Jersey during the 20th century.

By the 1940s, Horsman Doll was a great success on the basis of its moderately priced, good-quality, baby dolls that little girls loved.

The beautiful baby dolls came without fancy names (the child got to name her dolly whatever she wanted; the box didn’t provide a name) or marketing gimmicks, but dressed in lovely doll clothes. Harry was color-blind but he could tell fine fabric and excellent workmanship; he just needed employees to help him pick out the colors.

During World War II, shortages of raw materials dealt the American toy industry a serious blow. Some essential supplies were imported from overseas, including Axis territory and occupied countries. Kapok, for example, a fiber from the silk-cotton tree used for stuffing doll bodies, came principally from the Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies—and, of course, shipping of any kind was at risk. Most domestic materials, like the mohair for doll wigs and metal for sleep-eye mechanisms, were diverted to war industries, so little remained available for toy manufacturers.

Some toy companies began making products for the war effort. Horsman was able to continue making some dolls, but the Chambersburg factory turned part of its manufacturing floor over to soft vinyl prostheses, such as artificial hands for amputee veterans. After the war, most doll-makers scrambled to return to the production of dolls, but Horsman capitalized on its wartime experience with vinyl.

For all its advantages as doll-making material, composition was difficult to work with and it was hard to the touch. Vinyl was a soft, easily-molded, durable, unbreakable plastic that could be sculpted into life-like faces and was pleasing to a little girl’s touch. It was the perfect doll material and Horsman was a pioneer in its use in the doll industry. It wasn’t the first doll firm to use plastic, though in 1947 it was the first to do so on a large scale. From the post-war years until the Freeman family relinquished control of Horsman for the final time, its dolls were made with vinyl heads.

In the 1950s, Horsman developed an even more flexible material it dubbed Super-Flex, used for the dolls’ bodies, which for the composite dolls had been made of stuffed fabric and for the all-vinyl dolls were soft plastic that allowed for only minimal manipulation. Super-Flex permitted the dolls’ knees and elbows to be bent so the dolls could be posed in many different ways. Later in the ’50s, Horsman introduced further advancements in the dolls’ vinyl skin, giving it an even more like-like feel.

In the same decade, the company introduced Polly, an African-American doll. Horsman wasn’t the first doll-manufacturer to market a black doll—there were African-American dolls available in the 19th and early 20th centuries—but most of the earlier African-American dolls were merely models of the companies’ standard dolls from white molds painted dark brown. Horsman’s Polly was an attempt to create a black doll with more realistic features. She was sold from the mid-’50s through the 1970s and ’80s (the latter years by a derivative company that had duplicated Horsman’s original products).

Horsman dolls were seldom sold under the company name in the ’50s and ’60s. Horsman made most of its dolls for retailers like Sears, Montgomery Ward, Gimbels, and Macys and packaged them under the stores’ names.

By the 1950s, however, Harry Freedman and his now-partner, Larry Lipson, saw that the doll company had grown to its limit. It had supported the Freedmans and the Lipsons very well, but it wasn’t going to get any bigger.

Horsman made only baby dolls; it didn’t make “action figures” for boys or any other toys (not since the original Horsman family years) and it didn’t diversify its factory to make other plastic items (aside from that wartime foray).

Like most toy businesses, Horsman’s one big sales period, when it made its annual profit, was Christmas; the rest of the year, business dragged until it was time to gear up for the holiday gift season—and that wasn’t going to change.

Larry Lipson’s son, Gerald (1925-88), would take over the business when his father retired, just as Larry had taken over for Harry—but Gerry’s children were disinclined to run the company and Harry’s four grandchildren were still little kids.

So the shareholders—the Freedman and Lipson families and a few key Horsman employees, made the decision to sell the company. A conglomerate, Botany Industries, purchased Horsman Dolls in 1957 in a period of expansion.

The deal was standard. Botany agreed to pay off the purchase price over several years, and if at any point during that period Botany defaulted on the payments, Botany would forfeit all the money it had paid up to that time and the company would revert to the sellers.

And that’s what happened sometime in the early ’60s. Botany had decided that it had over-expanded and over-diversified and had to divest of several smaller acquisitions and downsize). So after paying off nearly the entire purchase price for Horsman, Botany backed out of the sale and the Freedmans and the Lipsons got the company back.

During the time that Botany owned Horsman, the Trenton factory was deemed outdated and beyond upgrading or retooling. So in 1960, Botany closed the Chambersburg plant and built a new facility in Columbia, South Carolina, a right-to-work state. That’s where Horseman dolls were made when the Freedman’s got the company back.

The plant in Trenton is now abandoned and, despite some interest a decade or so ago in converting it to residences, it remains unused. The developer who controls the property had proposed to raze the entire complex in order to build townhouses.

Not long after that trip to Columbia, the families put the company on the block again. Gerry Lipson was retiring and no one from either the Lipson or Freedman families was qualified (or interested) to assume control. This time, Drew Industries, another conglomerate, bought Horsman.

When the purchase was concluded, Horsman Dolls became Drew Dolls, under which name it produced dolls for a few more years, and then Drew Industries liquidated the company and Horsman Dolls, one of the last companies to manufacture dolls in the United States and never made them abroad, passed out of existence.

In 1986 the Horsman name was sold to Gatabox, Limited, of Hong Hong, which produced dolls, including reproductions of Horsman classics, under the name Horsman, Limited. The new company has no connection to either the original E. I. Horsman company or Harry Freedman’s business—Gata just bought the name. That company dissolved in 2002 but was succeeded by a new corporation known as Horsman, Limited, headquartered in Great Neck, New York, on Long Island and it continues to market dolls, but they’re made in Hong Kong now.