Excerpts From the New England Historical Society

Boston became the birthplace of the American Christmas card when Louis Prang, a failed German revolutionary arrived on its shores.

Louis Prang was an exile from the Revolutions of 1848 in the German States — a Forty-Eighter. The revolutionaries aimed to unify the German states. They also wanted to create a more democratic government and guarantee human rights.

By 1850 the revolution had failed. Prang therefore brought his dream of democracy and equality to Boston. He also invented the American Christmas card, which brought beautiful art to the masses, lucrative work to women artists and art education to children.

Children today still use the paints and crayons he developed more than a century ago.

Louis Prang was born March 12, 1824, in Prussian Silesia, the son of Jonas Louis Prang, a Huguenot textile manufacturer, and Rosina Silverman, a German. He apprenticed to his father and learned engraving, printing and calico dyeing. In the 1840s he traveled around Europe working as a printer and in textiles. By 1848 he was involved in the revolutionary activities sweeping Europe. The Prussian government targeted him and he escaped to Switzerland.

Prang married Rosa Gerber, a Swiss woman he met in Paris. He would later imprint his Christmas cards with a rose in her honor.

In 1851, he went to work for the engraver Frank Leslie in Boston. Five years later he went into business with a partner to create lithographs, specializing in prints of buildings and towns in Massachusetts. He became known for maps of the Civil War.

By the 1860s, a new color printing process allowed the commercially production of cards in England. The custom then spread, and Louis Prang caught on to it.

There are many stories about how Louis Prang decided to enter the Christmas card business. According to one, he went to the Vienna Exposition of 1873 and printed beautiful four-color business cards. An Englishwoman asked if he’d thought about printing Christmas cards. According to another, a clerk in his London office suggested he add Christmas greetings to his floral business cards.

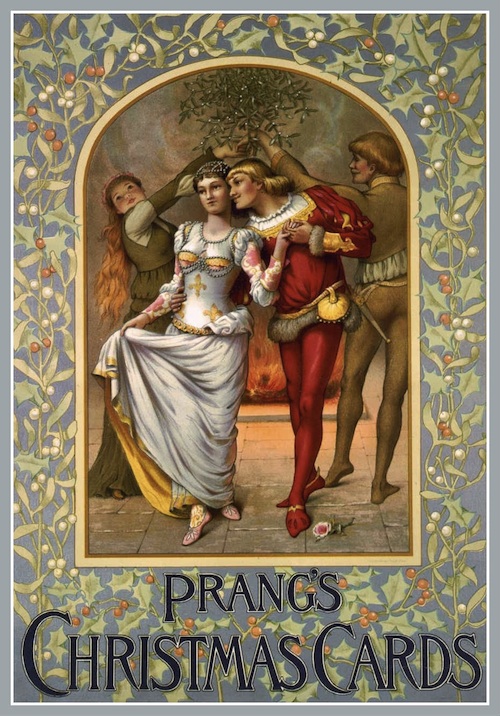

Whatever the case, Prang did some research and realized the enormous size of the potential market. In 1875 he printed his first Christmas cards and exported them to London. They were a big hit. The next year, he sold them throughout the Northeast. It took but two more years for him to corner the greeting card market in the United States. By 1881, he printed more than 5 million Christmas cards a year. His Prang Lithographic Factory in Roxbury became a tourist attraction, and he often conducted tours himself.

Collectors today still seek out Prang’s beautiful Christmas cards. They were printed on high-quality paper and lavishly decorated with as many as 30 colors applied to a single print. Some were embossed, varnished and embellished with fringe, tassels and sprinkles.

Prang signed them ‘L. Prang and Co.’ or just with a symbol of a rose. Young ladies recorded in their diaries how many ‘Prangs’ they received over the holidays.

Prang, he looked to women for help in finding new designs and keeping in touch with popular taste.

Women didn’t have many ways to make money outside of the home then. Decent occupations for women were limited to low-paying domestic service, teaching, millwork or sewing.

In 1870, Prang advertised his first art contest in the women’s rights journal Revolution.

He asked the Ladies’ Art Association to announce the contest to its members, select and judge the artwork and award the prizes. He then offered to buy any art that showed promise and to buy the winning artwork at the artist’s price.

He also bought paintings from women artists such as Rosina Emmet and Fidelia Bridges. He employed designers Lizzie Bullock Humphrey and Olive Whitney. By 1881, L. Prang & Company employed more than 100 women as designers, artists, finishers and embellishers.

Ten years after Louis Prang’s first art contest for women, he held another for Christmas card designs. The winners would have their designs published and share $3,000. Nearly 800 people entered the first contest in 1880, mostly women.

This was no ordinary contest. Prang exhibited the entries in the prestigious Doll & Richards art gallery in Boston and the American Art Gallery in New York. He then selected as judges architect Richard Morris Hunt, artist Samuel Colman and Edward C. Moore, Tiffany’s head silver designer.

The New York Times, commenting on the exhibit, noted a curious feature: the “utter ignorance of some of the competitors concerning the purpose of a Christmas card.”

Prang would hold three more contests for Christmas card designs, each one more elaborate than the next. The final exhibit traveled to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Institute of Art in Chicago.

European printers caught on to Prang’s approach. By 1890, they could lower their printing costs and then drive Prang out of the American Christmas card business with cheap imitations. But Prang refused to lower his quality.

He closed his lithographic factory and moved to Springfield, Mass., which had a large German population. He continued to produce high-quality work and made child-safe art materials.

In 1909, the American Crayon Company bought the rights to his art material, which eventually became Dixon Ticonderoga.

Louis Prang left another legacy: He brought art education to the American public schools. He published art textbooks and drawing books, taught art teachers and invented the ‘Prang Method of Instruction.’ The Boston school system used Prang’s methods for many years.

Louis Prang died on Sept. 14, 1909.