Exerted from the Cornwall Historical Society

One morning in the autumn of 1909, Edward Horsman Jr. had been stopped in his tracks by something he’d spotted the window of Brentano’s bookstore, a display of medallions — low-relief sculpted plaques — of children’s faces.

Earlier, the E.I. Horsman Co. had negotiated exclusive rights to a remarkable doll-making material, and its first Can’t ‘Break ‘Em’ composition head good luck charm, the Buddha-like Billiken, was a smash hit. Now Horsman Jr. hoped to follow that success with a whole new line of unbreakable composition children’s dolls.

Here, he thought, was an artist whose arresting bas-relief clay images caught the very essence of the American child, a person who could design the character doll heads he hoped to put on the market. Edward Horsman turned and walked into the shop. Inquiry soon took him to the portrait of the medallionist, Helen Fox Trowbridge.

In 1909, there was virtually no U.S. doll industry. Bisque-head dolls, imported from Germany, dominated the playthings market But Helen Trowbridge would change that. By the time the sculptress modeled her last prototype for the Horsman company in the early 1920s, American-made composition dolls were well established; the German monopoly was shattered.

Trowbridge, with her innovative and delightfully designed character doll faces, may be fairly considered as one of the most important but least appreciated contributors to the establishment of the early American toy industry. In little more than a decade, this talented sculptress designed scores of charming dolls. Because her designs – most of them produced in Horsman’s patented “Can’t Break ‘Em” composition – so caught the public’s fancy, they altered forever a child’s idea of what a dolly should look like.

Born in New York City, Sept. 19, 1882, Helen was the daughter of Dr. George H. and Harriet Gibbs Fox. Her lineage was long and prominent. On her father’s side, the Fox family traces its history to the eighth century and Charlemagne. The Gibbs line goes back nearly as far – an ancestor, Saire de Quincy’s name is on the Magna Carta – and is said to include crowned heads of a half-dozen European nations.

Helen’s childhood centered on the Fox family’s four-story home at 18 East 31st Street, between Manhattan’s Fifth and Madison Avenues. She grew up in a world of brownstone houses, like her own, with streets paved with Belgian blocks and filled with clip-clopping horse-drawn vehicles. In summer, Helen’s world expanded to include the homes of relatives and friends living mostly in western New York State, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Years later, Helen would recall her birthday in September 1885.

“On my third birthday … we were visiting at the time in my mother’s old home in Nunda (a small town in western New York) …. I was having my lunch alone in the cool, dark dining room … when there came a knock on the side screen of the room. It was a package the postman had brought for Miss Helen Fox. My mother, who was (at home) in New York attending to housepainters, had sent me a doll in my first parcel.”

From childhood, Helen demonstrated a talent for art and modeling, delighting in making figures from clay.

Helen was schooled at home by a tutor until she was nine, then was sent to a nearby private school. At 16, she went away to Ingleside, a boarding school at New Milford, Connecticut. Later she would say that she received a proper finishing school education there, meaning her education was expected to end with graduation. Nonetheless, she decided to pursue her longtime artistic interests.

She began her studies in October 1900 at New York’s Art Students’ League, but soon was discouraged. Her drawing was stiff and mechanical, she felt, inferior to most of the other students. Several months later, prematurely conceding defeat, she changed course, deciding to be a chemistry teacher. But there, too, she found herself ill-prepared by her finishing school education. She dropped out

and, as did so many other affluent young people of the time, traveled to Europe. It was a summer of fun and adventure, but also it gave her time to “find” herself.

When she returned home that fall, her goal was set. She resumed her art studies and quickly rediscovered her childhood enthusiasm for three-dimensional modeling. She studied at the New York School of Applied Design, then apprenticed with the talented American sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, who later would carve the massive features of four former U.S. presidents on South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore.

In New York, Helen launched her sculpting career. She visited hospital maternity wards, sketching newborns whose portraits she later would render as clay medallions, some of which also would be cast in bronze. She spotted other subjects, young children of all races and nationalities on the streets of Manhattan. With her “portable studio,” Helen was a common sight in the multi-ethnic, working class East Side neighborhoods.

In June 1909, she married Mason Trowbridge, a rising young attorney she had met four years earlier during a Yale football weekend. That was the same year she was contacted by Horsman Jr. Would she create character doll faces modeled from real, live American children? At first she hesitated. Redirecting her focus from portrait sculpting to toymaking was an unsettling choice for a serious artist. But, as she would admit in a newspaper article some years later, she was ready for a new challenge. Her answer was yes.

After their wedding, Helen and Mason Trowbridge moved into a $50-a-month rented bungalow on Vanderventer Avenue in nearby Port Washington, Long Island.

There they became good friends of a young couple living across the street, Hal and Grace Lewis. Soon, the rest of the world would know Hal by his name on the cover of his

bestselling novels, Sinclair Lewis.

Lewis would pen an affectionate inscription on the flyleaf of one of his first editions: ”To the Trowbridges, who took both the ‘nay’ and the ‘bores’ out of the once dreaded word, ‘neighbors’ …. “

Of Helen, Grace Lewis later would say, soon she was “producing babies with speed and casualness.” Her first child, Mason Jr., was born in Harriet was born in 1912; George, in 1916; Adaline, the following year; and James, in 1920. The Trowbridge’s sixth and last child, Cornelia, was born in 1922.

Shortly after her marriage, Helen set up a small studio in her Port Washington home and began sculpting dolls for Horsman.

In 1910, the company followed up on Billiken with its first real character doll, Baby Bumps, the result of Horsman’s decision to shun the old-fashioned, sweet but vapid-looking

German “dolly” faces.

But with Baby Bumps, the company still hadn’t broken free of the Teutonic influences, the doll bearing a resemblance to a Kammer & Reinhardt character baby. In introducing it, Horsman carefully chose a name that would emphasize that the doll’s unbreakable composition head could “take all kinds of bumps.”

It is uncertain if the original Baby Bumps was Helen’s work, but she did sculpt a number of variations in subsequent years. These included a 9″ Baby Bumps Jr.; a 17″ nearly life-sized infant and, in 1914, a slightly older Baby Bumps with a more grown-up smile and side-glancing eyes.

Perhaps Helen’s most successful doll head was the classic Campbell Kid, the cute and chubby little face that launched a billion bowls of vegetable soup. However, she received little credit for her sculpture since she had worked from the two-dimensional sketches- none, though, that showed a profile view – that Grace Gebbie Wiederseim (Drayton) had drawn for the Joseph Campbell Company.

In fact, for a time, though she’d designed literally dozens of character dolls for Horsman, the company itself didn’t publicly acknowledge her identity, referring to her, generically, as “an American sculptress.” But her talented eye and hands couldn’t long be denied and before long, the name Helen Trowbridge was appearing on Horsman’s design patent applications.

Of these early Can’t Break ‘Em character doll, one that seemed to stand out in her later recollections was the head she sculpted in 1911 using her own one-year-old son, Mason Jr., as the model. It was the first in a series that Horsman called the Gold Medal Baby.

Many of Trobridge’s realistic infants appeared in Horsman’s Nature Baby collection. One of those dolls, which also debuted in 1911, was called Baby Suck-A-Thumb, a curious name, since, because of the size and shape of its fingers, it could not! Helen rectified that problem with another doll in the Gold Medal Baby series, which was introduced for the 1914 Christmas season. Called simply, Suck-A-Thumb, it had side-glancing eyes and hair molded in a bit of a topknot, with an open mouth and a patented right arm and hand designed so as to simulate thumb sucking.

Although by this time Trowbridge had sculpted many composition heads for Horsman, it was her novel Suck-A-Thumb that finally brought her real public attention. She was featured along with other doll artists such as Margarete Steiff, Kathe Kruse, and Rose O’Neill, in a New York Herald article titled, “Sisters of Santa Claus,” which appeared shortly before Christmas.

“Between her love for her children and that of her work of toy modeling, Mrs. Helen Fox Trowbridge scarcely knows which makes her happiest,” the newspaper story said. That she was able to do much of her sculpting at home meant that she didn’t have to make the tough choice between working and being a stay-at-home Mom. Not surprisingly, therefore, the article noted that she was a “strong advocate of specialized home industries for women.”

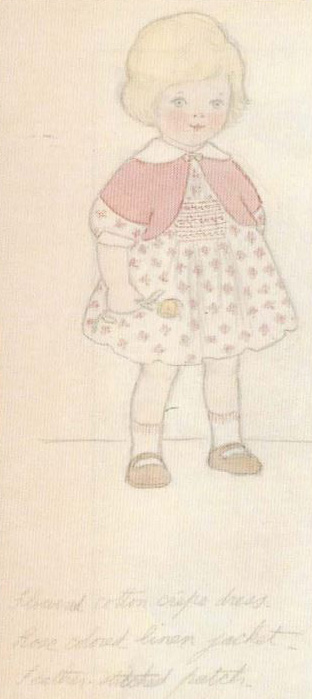

“Not satisfied with merely making dolls for Santa Claus’ pack, you may find Mrs. Trowbridge almost any day, when Jack Frost is not too active, sitting in her garden working on other things for children – book plates for the first library, wallpaper designs for children’s rooms, silhouettes and patented sanitary detachable covers for wooly lambs. She does statues of children at rest, children at play and at study.”

Although by 1916, Horsman was utilizing other sculptors – including a young Bernard Lipfert, who had graduated from painting doll heads for Horsman to modeling them – Helen was still the firm’s chief designer. It was a position she would maintain for at least several more years.

The Herald article makes it clear that Helen continued to find other artistic outlets, both commercial and purely personal, besides sculpting dolls.

A week before Christmas, 1918, the New York Evening Sun ran a story headlined “If All Doll-Babies Don’t Look Alike to You…Thanks Are Due to a Woman Sculptor.”

It was Helen Fox Trowbridge, the article explained, who was “responsible for the transformation to composition dolls which were more human, with “emotions and feeling to show like really-for-true babies.”

Trowbridge was interviewed in a small room in Horsman’s wholesale house on lower Broadway, where she was putting the “finishing touches” on a clay model of a two-year-old toddler. While it isn’t possible now to determine which doll this became, the reporter called it “different from any you have ever seen and more like a real child than any other. The expression is that of a youngster suddenly taken by surprise. The lips are half parted, the eyes wide open with delight, the soft cheeks just beginning to bulge with a coming smile.

“What I want to do,” Helen explained, “is to get the makers to turn them out more in proportions of real children. But it is hard to make a superintendent of a doll factory understand that it is desirable to make a baby doll with arms that extend below the waistline, or with legs in tur physiological proportions to the body. They have never done it. Therefore they will not believe that any one really wants them to do it save, perhaps an exceptional artist with ideas unshared by the juvenile public!”

Had Helen Trowbridge moved too far and too fast for Horsman or any other company? It seemed so.

“What I want to do” she said, “is to get back to my real work, the work I left to do this; the work that is better and more worthwhile and what I started in the first place to do.”

But then, the newspaper article continued, her ambivalence became apparent. A certain light came into her eyes. She paused, and continued, quietly: “But it’s the hardest thing to drag yourself away from these!”

After this, Helen Trowbridge designed few new composition dolls. But one of them clearly was a favorite, the Jackie Coogan Kid, her only celebrity doll. Charlie Chaplin discovered young Jackie, then only 4, in 1917. After appearing in a series of silent shorts, he found stardom in 1921 as the quintessential waif, playing opposite the great Chaplin in ‘The Kid.”

The 7-year-old boy was a smash hit, and Horsman quickly signed a licensing agreement to produce a Jackie Coogan Kid doll. Trying to cash in quickly, the dollmaker redressed an existing doll, one that had been on the market for seven years, and called it Jackie Coogan. But that was just a stopgap.

Trowbridge was commissioned to do a new doll head, one that looked like the child star, complete with his Dutch boy haircut. Young Coogan actually sat for Helen who made sketches and measurements. Though the result was a remarkable likeness, Horsman felt it made The Kid look “too shrewd and too old a type to be pleasing.” The likeness was modified to make a more pleasing doll.

One of the last of Trowbridge’s composition dolls was Bye Bye Baby, a unique doll whose arms could, with the pull of a string, move in a lifelike manner, imitating a baby’s gestures. It was made of Adtocolite, Horsman’s for the improved hot pressed wood fiber composition, which, a half dozen years earlier, had replace the old Can’t Break ‘Em type compo. The new material and technique allowed the company to produce better dolls faster and cheaper that before.

But Helen, by her own description, always “a designing fool,” hadn’t abandoned an interest in creating dolls. For some time she had been intrigued by the possibilities posed by cloth dolls. Even as a child, she had created rag dolls for herself and her young friends.

In 1918, after the Trowbridges had moved to Upper Montclair, New Jersey, she designed a cloth baby doll with painted face. She recruited local high school girls to cut and sew the dolls. The project gained momentum, a workroom was rented, and hundreds of dolls were produced. They were sold, with the profits being contributed to a wartime charitable fund directed by author Edith Wharton. Horsman later took over Helen’s project, paying a percentage of each sale to the war relief fund. Helen continued to design new cloth dolls for Horsman’s Babyland Rag series, which continued into the 1920s.

In a 1936 newspaper article, Helen said: ”It is very funny, but I like to maintain I am the only woman who at one time earned a living by not knowing how to sew. I began to work on the rag doll de sign and hadn’t the

faintest idea how to cut a sleeve. I had to design it so simply that it was no effort for the operators to turn out, consequently it was most successful.”

Her rag doll Patty-Cake was distributed by Horsman for about eight years, with variations known as Baby Patty-Cake and Pat-A-Cake, which allowed the child to insert a hand in the back of the doll to make it clap in delight. In 1922, Trowbridge was issued a design patent, which she then assigned to Horsman, for another rag doll with yarn hair and side-glancing eyes. With that, though, she seemingly ended her commercial doll-designing career, although she would continue to promote homemade craft toys for the rest of her life.

In 1916, Mason Trowbridge had left his law practice and joined toothpaste and soap maker Colgate. He would be associated with Colgate as the corporation’s general counsel until his retirement. Over the years, the family lived in Port Washington, then moved to Glen Ridge, New Jersey, then, to nearby Upper Montclair. Later the Trowbridges would live in Chicago for a half dozen years, but then returned to New Jersey.

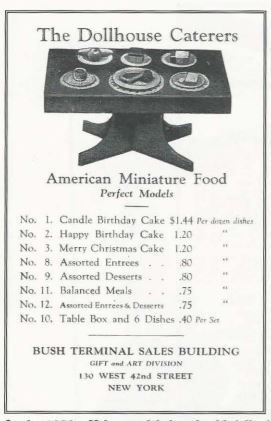

Helen launched a new venture in 1934, making and selling in a New York shop miniature dollhouse accessories. She fashioned wee potted plants, sets of alphabet blocks small enough for a doll to play with, scaled-down tables and lamps, even a tiny candle that glowed. She particularly enjoyed creating mini meals, more than 30 different kinds of dolly-sized foods, everything from plaster pies to casseroles of browned baked beans – painted birdseed, actually. Though unique, this business survived only a few years.

Mason retired in 1946, and the couple moved to an apartment in Manhattan. In 1954, the couple moved to West Cornwall, Connecticut. In March 1962, Mason died at the age of 84. Helen survived him by eight years. On July 27, 1970, she died following a short illness. She was 87. Survivors included four of her children and 12 grandchildren.

Her death went unnoticed by the huge American toy industry that her early work had helped to spawn. A tiny obituary in the New York Times noted merely that “Mrs. Trowbridge, the former Helen Fox, designed dolls

for Horsman Dolls.”